A Conversation with Shaikh David Bellak

Here is a memory of an evening of spiritual conversation, called "sohbet" in Turkish, with Daud Bellak over twenty years ago in his home in the New Town of Edinburgh. It expresses something of his teaching, and a story from his own teacher, Suleyman Hayati Dede...

The Conversation

It was a pleasant weekend in late Summer 2003. A friend of

mine named Lili from Bern in Switzerland was over visiting, and we drove up

from Sheffield where I was then living, through the Lake District and on to

Scotland, where we spent a couple of nights. The first evening we were invited to

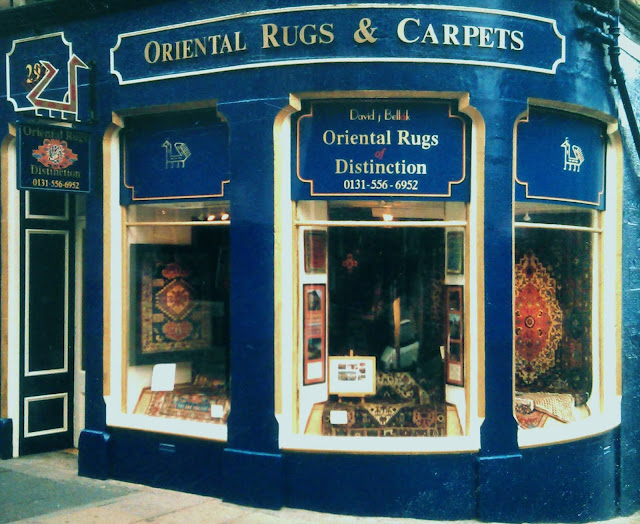

dinner with David Bellak, shaikh and whirling dervish in Rumi’s sufi tradition.

David lived in a comfortable ground floor flat in

Edinburgh’s New Town - which is not new at all, but actually a historic UNESCO

heritage district of Georgian and Neo-Classical buildings, constructed from

local sandstone. It’s new relative to the medieval Old Town up the hill, famous

for the Royal Mile running from the Castle down to the Palace of Holyrood.

I knew David was an excellent host and he was generous in welcoming

guests. To the three of us were added two theatrical friends of mine from

Glasgow University, Liam and Matt, who had performed in several productions I

had directed there and were now pursuing postgraduate studies. Matt later went

on to lecture about art to science students at Imperial College, London. Liam,

true to his free-spirit, wandered in search of community and friendship.

Liam and Matt, like David, were tall and lanky, and known

for their boyish good looks. Many an arts student in Glasgow had fallen for

their charms. Lili too had a charm about her, though smaller in height and build. She had been a junior equestrian champion in Switzerland, and owned a

big black horse called Otello. She now worked as an events manager throwing lavish parties for big businesses.

David welcomed us with customary warmth and we sat around

the polished wooden table in his living room. He had cooked a small feast! The

main course was some kind of pilaf, and there was a lovely platter of grated

carrots in lemon juice surrounded by tomatoes. We ate and talked, the usual

social chatter, in an ample sized room with small oriental weavings and fine

art photographs decorating the walls. The photos were by David himself. On

leaving the US Navy where he had been conscripted in the Vietnam War, he

pursued a Master of Fine Arts degree in photography and took photos all over

the world. I first encountered the work of Ansel Adams through David, and later

Henri Cartier-Bresson. David explained photography as seeing something more

“real” in a scene, the image somehow isolating and conveying it to the viewer.

It’s not far from this idea of the “perception of the real”, to the idea of

spiritual vision perceiving the Real. David often quoted a line found at Rumi’s

tomb in Konya – “This way is the real way”, or, “This is the way of the Real”.

After dinner, still sitting around the table, the

conversation became more reflective and the evening grow close. Lili’s phone

rang, and she excused herself from the table, and Matt and David – these two

tall, dark and mysterious men, separated by a lifetime in age - were drawn into

deep conversation, or “sohbet” as it’s called in Turkish sufism.

The conversation began through the topic of intuitive

knowledge. Matt had been talking about following stars, perhaps in reference to

ancient sailors. David used this analogy of astral navigation as a way in to

addressing the knowledge in sufism - perception in and through the heart rather

than the intellect alone. He proposed the existence of “another world” beyond the

one we generally perceive, and described sufism as a path that includes and integrates

both worlds.

Briefly he touched on the need for esoteric “schools” to

function as a “mirror” for the student, one that reflects our inner states and blind spots accurately, instead of distorting in the way our habitual self-image

does. His first discovery of the idea of a School was in the Don Juan books of

Carlos Castenada, which he read in the 1960s. Don Juan was a Mexican shaman and

sorcerer, and Castanada his would-be apprentice. David told us the story of Don

Juan meeting Carlos and directly forcing him to experience the other world, because

“we only have an occasional square centimetre of chance” in our lifetime. These

chances are there for everyone, but are we aware enough to notice them if they

arise?

David spoke then of the need to be “conscious”. This was a

word he used often, sharing in some sense both the sufi idea of Remembrance of

God – zikr’ullah – and the teachings of G. I. Gurdjieff on “self-remembering”.

Our attention is mostly bound tightly with our internal responses to the world,

and propels us as if mechanically in a ceaseless procession of

cause-and-effect. If instead we can drop this attachment to our responses and

become more freely, even innocently, aware of what’s taking place, and even

further, if we attend to our sense of the one who is present in us, then a new “substance”

begins to become available to us. This substance – call it the substance of

light, call it holy presence – is kneaded together with the stuff of our body

and our mind and transforms us, inwardly and outwardly, into something more

than we were without it. “We build this body, cell by cell like the bees”,

sings Rumi. This new body, a body of light, belongs to that other world David

had spoken of.

Lili was still on her phone in the hallway. I wondered if

she had decided she was too tired for deep conversation after driving all day.

Matt continued to question David, while Liam and I sat listening intently

across the table. We were seated in the pattern of a cross – Liam opposite me,

Matt to my left, David to my right.

Settled well into a flow now, David told three stories. The

first was of his own teacher, the late Suleyman Hayati Dede, apparently

magically serving endless amounts of rice from a nearly empty pot. The second,

of a friend who travelled the world seeking spiritual truth, but who was always

sceptical – and how it took a Himalayan yogi manifesting a physical object out

of thin air to convince him.

And then a story from Suleyman Dede…

… One day an important teacher came to the tekke, the

sufi lodge. The students all assembled and waited to hear him talk. But for a

long while he was unable to speak… Finally, in angry tones, he blurted out,

“Who here is not one of us?!” The students looked around, but could see no

strangers among themselves. And so the silence continued, until once again the

teacher erupted, “Who here is not one of us?!” Once again, the students

looked around but could see no one. “We’re sorry”, they said, feeling uncomfortable

and embarrassed, “but everyone here is one of us.” And so the silence continued

awkwardly, until finally the teacher bellowed, “Whose is that?!!” –

pointing to a walking stick near the door. The students explained that it

belonged to a man who had visited the tekke the day before – he’d left it

behind, but they didn’t like to move it out of respect for someone’s property.

“Get it out! Get it out!!”, the teacher demanded. “Even sticks have ears!”

I didn’t really understand this story, even though I’d heard

David tell it several times before. Perhaps it made sense to me as a warning to

have the appropriate company for spiritual teachings. Now I think it may point

also to everything having its place in the worlds, inner and outer, and it

matters that things are in their right places. Worlds have their own structure

and meanings, to be seen and understood by conscious hearts.

Having travelled deep into the mysteries, taking us with

him, David returned to the mind and our need for a map. He spoke of there being

seven levels of spiritual growth – three lower levels associated with our automatic, unconscious nature, and four higher ones. He said people on a lower level can’t

understand the experience of the higher levels, but that someone on the fourth

level can at least appreciate the language and terms used by those on higher ones.

The spiritual life is a kind of evolution, one that we consciously participate

in.

David also spoke of the importance of the teachings of Gurdjieff

in helping develop an attitude and vocabulary appropriate for the Western mind,

and said this had come to form part of his spiritual vehicle. Reflecting on

this later, I wondered if perhaps this was one role of Buddhism for me – that

it had helped give me a context for understanding sufi ideas and applying them

in my life, which I might have found more difficult otherwise.

Overall, David seemed well that evening I observed – full of

light and warmth, and with a gentleness softening his characteristic directness

in speech and manner. The flat was beautiful and welcoming as always, and the small

garden was coming on well. David said he did ten minutes gardening in the

mornings before going to work.

Before we left, he stressed to me the importance of keeping

my word, and said that some people would go to the ends of the earth to avoid

breaking it.

CS

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment