Memories of the Mihrab Gallery

It was January 1999. I had just returned to Glasgow

University in September, after an earlier false start and a three-year

incursion into Buddhism, including highland retreats, life in communal houses

and theatrical exploits. Looking for books in the university library on Sufism,

which I had begun to explore the previous year, I found Shems Friedlander’s The

Whirling Dervishes with its darkly evocative pictures of dervishes in white

against black backgrounds, and I found a website – searching the internet was

still quite a novel experience back then! - for the Threshold Society in the

USA, a sufi organisation connected to the Persian mystic and poet Jelaluddin

Rumi. They offered a distance learning introduction to sufi thought and

practice called the 99 Day Program, which I wrote off to join, and in writing I

happened to ask if they knew of anyone in Scotland also practicing. The

Threshold secretary, David, wrote back and told me there was a man, also called

David, a teacher in the same tradition, who ran an oriental carpet shop in

Edinburgh. “Aha!”, I thought - because I knew the very place.

Four years earlier I had lived in the centre of Edinburgh,

renting a room in an apartment beside the Assembly Rooms on George Street. I

worked for a while in a shoe shop on Princes Street, then temporarily found telemarketing

work further out of the city centre, cold calling on behalf of a double-glazing

firm. I used to run to work to get fit, and my run took me along the Royal Mile

and past Holyrood Palace. Along the way was a small oriental carpet shop which

fascinated me – I sometimes stopped outside and felt drawn to go in. I had no

reason though to actually go in, and I only ever saw one or two people inside,

so my shyness won out and I kept running.

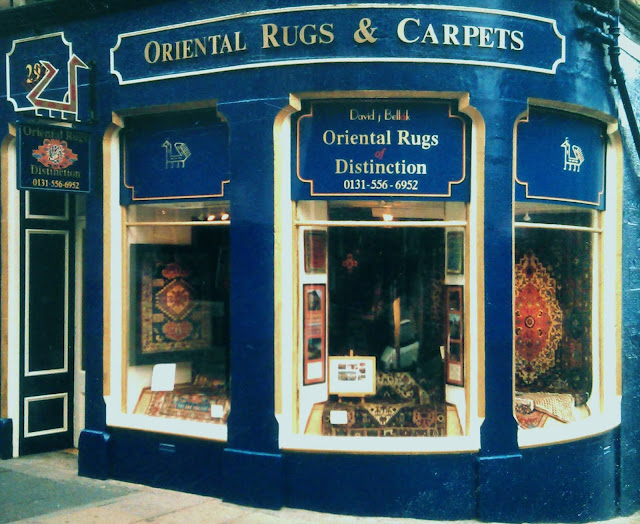

There was something about the shop though. For the past few years I had worked on and off as an experimental theatre director, involved with student theatre at Queens University in Belfast, then setting up my own company in Derry. My inspiration was the British theatre director Peter Brook, who I learned later was a dedicated student of the spiritual teachings of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, the Russian-Armenian mystic. Something about the carpet shop on the Royal Mile gave me a strong sense of Peter Brook’s work. This turned out to be an uncanny coincidence, because the David J. Bellak who ran it had strong connections not only to Sufism, but to the Gurdjieff teachings too!

It’s hard for me now to separate out the different layers of

memories of visiting David’s shop, the Mihrab Gallery, over many years. Through

it all, the memories evoke a tangible sense of spiritual beauty. The rugs

hanging on the walls, some laced through with silken thread, woven in bright

colours, subdued colours, simple or ornate, small or immense, each with

geometric patterns radiating out from a central motif that seemed to say “The Many

proceeds from the One”, all diversity of shape and hue brought into harmony and

coherence through that central point. And in the window – had I noticed it

subliminally four years earlier? – a small porcelain Whirling Dervish, arms outstretched

to the heavens.

It was as if the interior of the gallery awoke and mirrored

the interior of my being, reawakening me to a light and structure within me,

the tangible presence of spiritual handiwork. The human inwardness is a mirror

of the Divine Attributes, if we can but get ourselves out of our own way, stop

standing in our own light. Love, Beauty, Compassion, Wisdom, Strength and Grace

– all shine through our heart if we clear away the dust obscuring its shining

face.

I have no memory of how I introduced myself to David, whether

I had phoned through in advance or decided just to bravely walk in and say,

“Hello! I’m told you’re connected to Sufism…” What I do remember is asking him,

on one of my first visits, how exactly he ended up involved with the spiritual

path. His answer was indirect and mysterious, framed as it was by the intricately

patterned carpets on the walls and floor, yet also simple and honest. “How does one

end up anywhere?”, he responded. Although we can give explanations, accounts of

our journey, in the end it is a mystery, we are brought to where we are

supposed to be.

On another of those first visits, David took me out of the

shop and a little further back up the road in the direction of the Castle. We

went into a small, dimly lit traditional Scottish pub on the same side as the

gallery, where he offered to buy me a drink. I asked for a pint of Guinness. He

spoke of Rumi’s Way as being less concerned with religious externals and

formalities compared with some other Sufi schools, such as the Naqshbandi, who

he said were known in Turkey as “The Keepers of the Law”. It was the only time

he ever did such a thing – take me to a pub and buy me a beer– but it was

enough to make a point and prevent me ever developing a rigidly religious

persona as I was drawn deeper into Sufism and the worlds of Islam.

Two other things about the shop I should mention. First,

there was a CD player by one wall not far from the entrance, and I remember

hearing the Arabic instrument called the oud for the first time on one of the

CDs – ‘Barzakh’ by Anouar Brahim. Second, that in one of the drawers of David’s

desk, he kept a copy of the Discourses of Rumi by A.J. Arberry, a

translation of the conversations of Rumi as recorded by his students.

David knew I was studying the Threshold Society’s 99 Day

Program, and in fact he had visited the founders of Threshold, Kabir and

Camille Helminski, in the USA the previous year. This was a very painful period

in David’s life, having just divorced and seen his wife and children leave the

UK to live in the US. He was to have little contact with them for many years.

He told me how he had sat in tears in the home of the Helminskis, overwhelmed

by grief. When I mentioned that the 99 Day Program had introduced the

recitation of “Estaghfirullah” – ‘May God forgive’ - he sighed with genuine

pathos, “Ah, Estaghfirullah!”

One day, I don’t remember how many times I had visited by

then, David invited me down into the spacious store room beneath the gallery

floor, and there he recited with me for the first time the Mevlevi zikr as he

had received it from Suleyman Hayati Dede in Konya. It is such a simple zikr,

yet with such depth and with subtlety in the rhythm and recitation. How

wondrous and mysterious that this zikr has come down to us, down through

centuries of Seljuk and Ottoman rule, and through the decades of Sufism’s

suppression in modern Turkey in the Twentieth Century.

What is zikr, though? At that time I experienced it simply,

without complication. It was a recitation of words in Arabic that served to

connect me to the heart. David spoke sometimes of “coming”, of “bringing the

heart to the Kaaba”, when evoking the intention for gathering in community and

practicing zikr. It’s something we actively choose to do, or at least we

consent to be drawn, as I was to the gallery. You might say, this is the very

heart of “the Work” in Sufism and in Gurdjieff’s teaching: we make the simple,

naked effort to show up, to be present, to be conscious with what unfolds. There

is no compulsion in religion – we tread the way freely with each conscious step.

The fruit of the Work comes not through our own efforts, but through the grace

of God.

I found then, as I still find now, that practicing zikr

seems to bring about an orientation within me, like the pattern on the oriental

rugs organised around a central point. With zikr, I am more whole, more

coherent, more centred, more rooted, and the outer life around me seems that

way too. Without it, I become fragmented, lost in anxiety and a hopeless quest

to understand life conceptually. In my experience, the Mihrab Gallery formed a

central point in the pattern of my life, reminding me of Divine Unity and of my

true self.

CS

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment